EU's Pushbacks of Asylum Seekers in Aegean and Mediterranean Seas

by Ana Grolli

Pushbacks, the practice of forcibly returning asylum seekers and migrants at borders, have become increasingly controversial and concerning, within the European Union (EU). In this short article, we examine the legality and implications of pushbacks, mainly in the Aegean and Mediterranean Sea, highlighting the human rights violations and breaches of international law that often occur. It also explores the challenges faced by EU member states in seeking a collective and effective response to addressing the issue of migrants and refugees, considering the legal, humanitarian, and political imperatives at play. We also analyse potential solutions and measures to ensure respect for migrants’ fundamental rights and compliance with EU and international legal obligations.

In recent years, the Aegean and Mediterranean region has become a focal point for migration, with thousands of individuals undertaking perilous journeys across their waters in search of safety and opportunity. However, alongside this migration flow, a troubling trend has emerged: the practice of pushbacks. Pushbacks refer to the interception and forced return of migrants and asylum seekers attempting to cross borders. While the European Union member states and other countries justify pushbacks as necessary for border control and security, critics argue that they represent a breach of human rights, international law and humanitarian principles.

Frontex

Before we delve into the subject of pushbacks, we need to understand the EU agency responsible for coordinating and managing border control efforts across member states known as Frontex. Established in 2004, Frontex, formally known as the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, aims to ensure the security of the EU’s external borders, facilitating legitimate travel and trade, and combating irregular migration, human trafficking, and other cross-border crimes. In recent years, Frontex has been accused by several international organisations of international law violations such as alleged complicity in non-refoulement violations and reports of excessive use of force during border enforcement operations.

The Pushbacks

The pushback practices involve forcibly returning asylum seekers and migrants across borders without regard for their individual circumstances or their right to seek asylum.

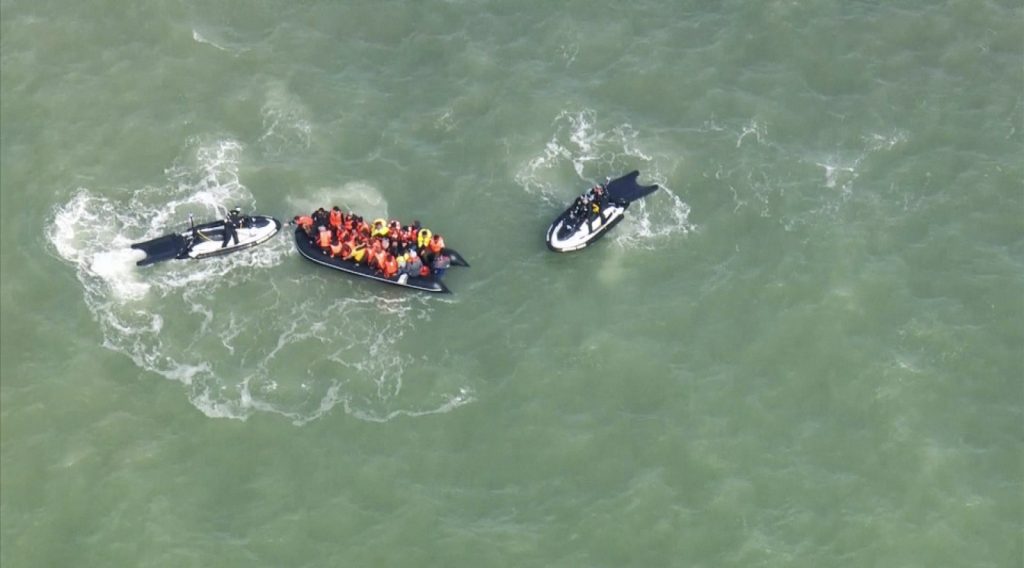

Vessels operated by Frontex have been implicated in maritime “pushback” operations aimed at deterring asylum seekers and migrants from entering the European Union via Greek and Italian waters, according to a collaborative investigation by Bellingcat, Lighthouse Reports, Der Spiegel, ARD, and TV Asahi.[1] Furthermore, open-source data indicates that Frontex assets were directly involved in several pushback incidents at the Greek-Turkish and Libyan-EU maritime border in the Aegean and Mediterranean Sea. Given that the distinctive signature of pushbacks would likely have been detectable through radar or visual observation, this raises questions about Frontex’s complicity in these operations.[2]

In the Aegean and Mediterranean Sea, pushbacks typically occur in two forms: either by preventing dinghies from landing on Greek or Italian soil through various means, including physical obstruction or disabling engines, and then pushing them back into Turkish or Libyan waters; or by detaining individuals who have managed to land, placing them in a liferaft without propulsion, towing them into the middle of the Aegean and Mediterranean Sea, and abandoning them. Such actions often lead to dangerous standoffs between the Greek Coast Guard, The Turkish Coast Guard, The Italian Coast Guard and the Libyan Coast Guard, all of which refuse to aid distressed dinghies and engage in risky manoeuvres around them, further endangering the lives of those on board.[3]

Legal Framework

Article 33(1) of the 1951 Refugee Convention establishes the fundamental concept of non-refoulement, meaning that states are prohibited from forcibly returning asylum seekers to a place where their life or freedom would be in danger due to factors like race, religion, nationality, social group, or political opinion. The violation of this principle is also commonly known as pushbacks. This principle has become a widely accepted customary international law, preventing any exceptions or reservations, particularly in situations of large-scale migration.[4] Non-refoulement is enshrined in various international treaties, including the 1951 Refugee Convention and the European Convention on Human Rights. Despite these legal obligations, pushbacks continue to occur, raising questions about accountability and adherence to human rights standards.

Even though the principle of non-refoulement directly violates pushbacks, other legal instruments also condemn them, for instance, the customary duty of states to aid individuals in distress at sea, as outlined in Article 98(1) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This obligation mandates ship masters flying a state’s flag to assist those in danger of being lost or in distress at sea promptly. While the duty encompasses all vessels capable of providing assistance without risking their safety, it’s essential to define what constitutes ‘distress.’ According to established jurisprudence and the 1979 Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue, a ‘distress phase’ occurs when there is a clear and immediate danger to individuals or vessels requiring urgent aid. The EU, having signed UNCLOS in 1984 and ratified it in 1998, inherits these obligations. Additionally, EU bodies are bound by both customary international law and EU legislation, such as EU Regulation 2019/1896, to provide assistance to those in distress at sea.[5]

Pushbacks not only violate the rights of migrants and asylum seekers but also pose significant risks to their safety and well-being. Many individuals attempting to cross the Aegean and Mediterranean Sea are fleeing conflict, persecution, and poverty, and pushbacks only exacerbate their vulnerability. Reports of violence, abuse, and neglect during pushback operations highlight the urgent need for accountability and oversight.[6] Many deaths have also been reported, inclusively by the United Nations. [7]. Moreover, pushbacks contribute to a culture of deterrence that fails to address the root causes of migration or to offer sustainable solutions.

The necessity of safe passage and safe routes.

One of the biggest obstacles for asylum seekers to travel on safe routes is the inaccessibility of visas. Even though such a barrier exists, the principle of not requiring visas for asylum seekers is generally derived from Article 31 of the 1951 Refugee Convention. This article stipulates that States parties shall not impose penalties on asylum seekers who enter their territory “irregularly”, as long as they can demonstrate that they are seeking asylum and have valid reasons for doing so. This is known as the principle of non-penalisation for irregular entry. Although Article 31 does not specifically mention visa issues, it is interpreted as encompassing the protection of refugees who may be prevented from entering a country due to a lack of valid travel documents.

Even so, we still see people taking irregular routes and trying to pay smugglers to seek asylum. An asylum seeker is not allowed to embark on a plane to Europe without presenting a visa, which goes against the above-mentioned convention. The inconsistent application of the Asylum Procedures Directive (Directive 2013/32/EU) remains a major obstacle to achieving solidarity among EU Member States. Various studies highlight numerous factors contributing to the EU’s struggle to establish a fair and effective asylum policy. Some countries adopt minimal standards to deter asylum seekers, sparking competition among Member States and leading to a “race to the bottom” where states vie to offer the least assistance. Disparities persist in asylum recognition rates, administrative procedures, legal frameworks, protection measures, and reception conditions, fostering secondary movements and rule abuse. This situation results in human tragedies, asylum seekers’ frustration, profiteering by smugglers, negative public attitudes toward migration, diplomatic tensions, and wasteful border control spending.[8]

A lot of EU countries are working on the externalisation of proceedings of asylum-seeking. The UK is spending billions of pounds on the “Rwanda bill” to send its asylum seekers to wait for a decision in another country, instead of developing quality public policies to process their claim in the UK. Several times the British Supreme Court has already considered the bill illegal.[9]

To establish safe routes for asylum seekers, governments and international organisations can implement a range of solutions, including increasing resettlement programmes, issuing humanitarian visas, engaging communities in sponsorship initiatives, fostering regional cooperation, supporting frontline states, expanding family reunification opportunities, providing legal pathways for employment, and enhancing sea and land rescue operations. These measures aim to reduce the reliance on dangerous migration routes, prevent loss of life at sea, and ensure that asylum seekers can access protection in a safe and dignified manner.

References:

[1] WATERS, Nick, FREUDENTHAL, Emmanuel and WILLIAMS, Logan. “Frontex at Fault: European Border Force Complicit in ‘Illegal’ Pushbacks”. Available in:

https://www.bellingcat.com/news/2020/10/23/frontex-at-fault-european-border-force-complicit-in-illegal-pushbacks/ Accessed on: 18/03/2024.

[2] Ibid 1.

[3] BARNES, Jamal. “Torturous journeys: Cruelty, international law, and pushbacks and pullbacks over the Mediterranean Sea”. 2022, p 446.

[4] GRAF, Jan-Phillip and BUDELMANN, Kai. “A pushback against international law?”. Available in:

https://voelkerrechtsblog.org/de/a-pushback-against-international-law/ Accessed on 18/03/2024.

[5] Ibid 4.

[6] The Guardian. “Revealed: 2,000 refugee deaths linked to illegal EU pushbacks.” 05/05/2021. Available in:

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/may/05/revealed-2000-refugee-deaths-linked-to-eu-pushbacks. Accessed on: 18/03/2024.

[7] UN News Global perspective Human stories. “Latest Mediterranean deaths highlight the need for safe migration routes.” 29/01/2024. Available in: https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/01/1145997. Accessed on: 18/03/2024.

[8] ANGELONI, Silvia. “Asylum Seekers in Europe: Issues and Solutions”. 2018. Available in: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12134-018-0556-2. Accessed on 18/03/2024.

[9] BBC. “What is the UK’s plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda?”. 19/03/2024. Available in: https://www.bbc.com/news/explainers-61782866. Accessed on 19/03/2024.